The aboveground bunker and its history

How can a hermetic structure like an air-raid bunker become an open environment for new encounters? Can a landmark with such a grim history become a dynamic art space? What transformative processes could change a solid structure of concrete into a unique complex of residences and offices that give something back to the city? An examination of the construction and use histories of the aboveground bunker at Ungerstraße 158 in Munich reveals Germany’s past and a carefully considered example of historical preservation.

1940 until 1945

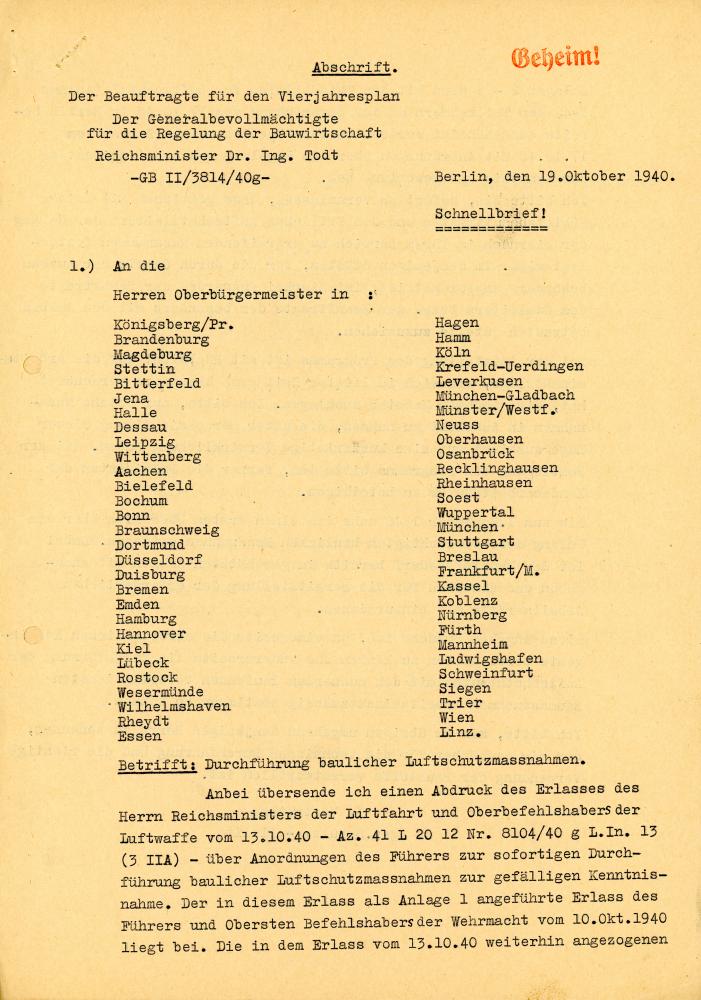

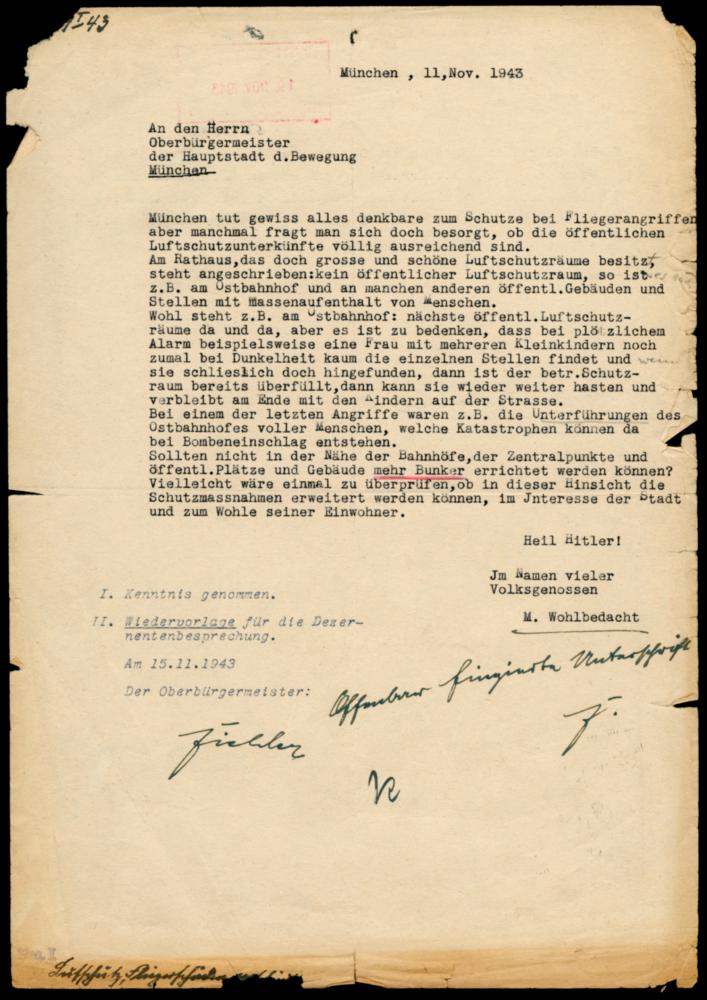

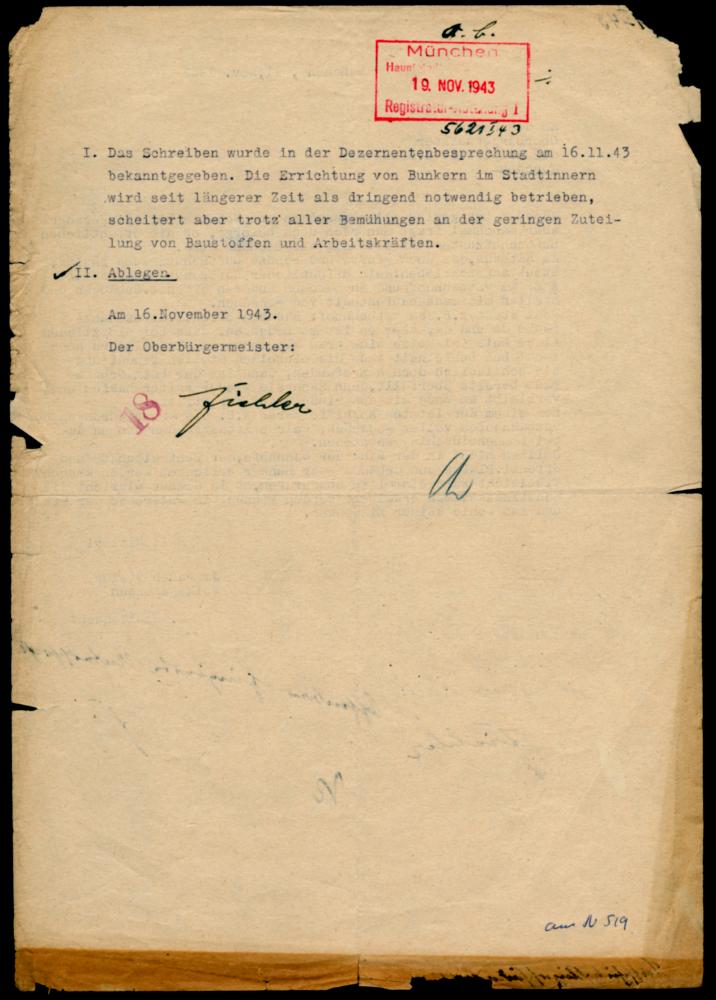

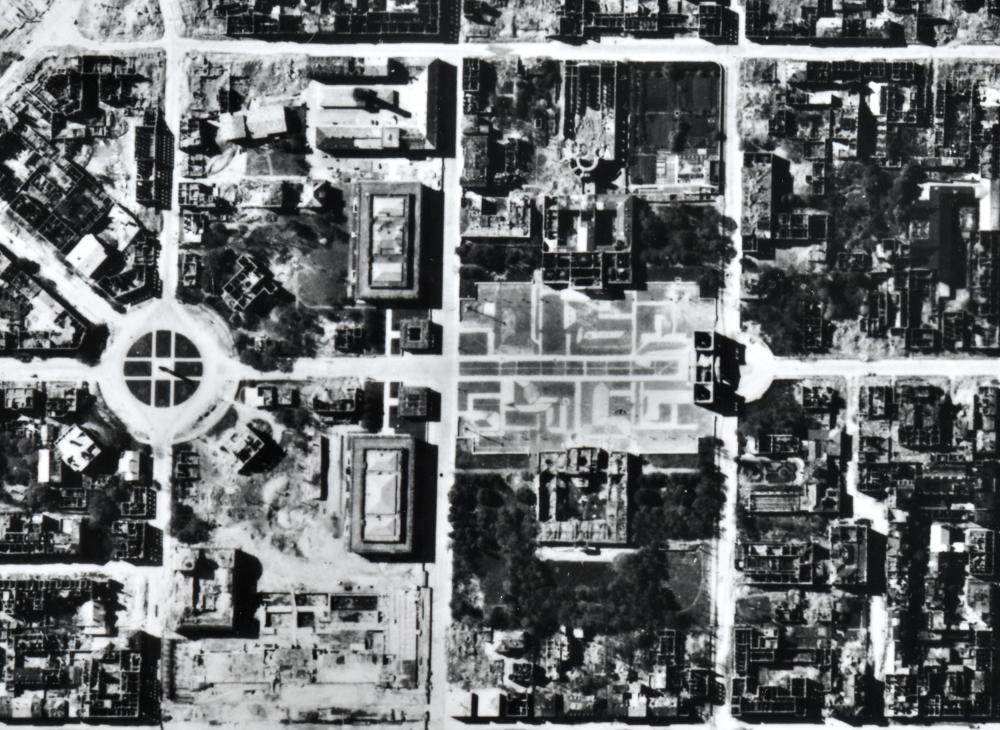

In reaction to the first air raid on Berlin by Allied forces during World War II, Adolf Hitler enacted the so-called Führer-Sofortprogramm (Leader’s Emergency Program) on October 10, 1940. With this order, he mandated the planning and construction of air-raid bunkers in over sixty cities within the German Reich that were considered to be most at risk of attack. Munich, of course, was part of this plan, both because of its symbolic significance as the seat of the NSDAP (National Socialist German Workers’ or Nazi) Party and its strategic importance as the headquarters for war-related industries like BMW, Dornier, and Kraus Maffei. Until the end of the war, the Munich Stadtbauamt (Municipal planning office) oversaw the construction of around forty aboveground bunkers, and the bunker in Ungererstraße was one of them. In comparison to underground shelters, the aboveground bunkers were cheaper, required less time to build and provided comparable levels of security.

Completed in 1943, the bunker in Ungererstraße demonstrates the architectural design and urban development considerations that went into its planning. In addition to their practical purposes, the air-raid protection towers constructed during this period assumed an important function as inwardly directed tools of propaganda: while giving citizens a sense of personal security, they also assured the public of Nazi Germany’s readiness to withstand Allied attacks. The Renaissance elements on the facade, the wraparound bench at its plinth, and the ashlar masonry at its corners fit into the larger prograndist vision of Munich as the Hauptstadt der Bewegung (Capital of the Movement).

With two-meter-thick walls and an equally massive roof plate, the seven-story, solid concrete structure provided protection for initially 657 and later 702 people. In close proximity to the bunker, military barracks, the repair centers of the German Reichsbahn, and important technical industry facilities like the Süddeutsche Bremsen AG, Bavarian Leichtmetallwerke, and BMW were located in the city’s northern section. In the event of a sudden air raid, employees of these companies on their way to work would have been able to seek shelter in the bunker. Additionally, the mostly undeveloped area around the nearby Nordfriedhof cemetery made it possible to use the elevated structure as an anti-aircraft defense tower, a function that is indicated by a port for loading munitions into the building on the western facade.

1945 bis 2010

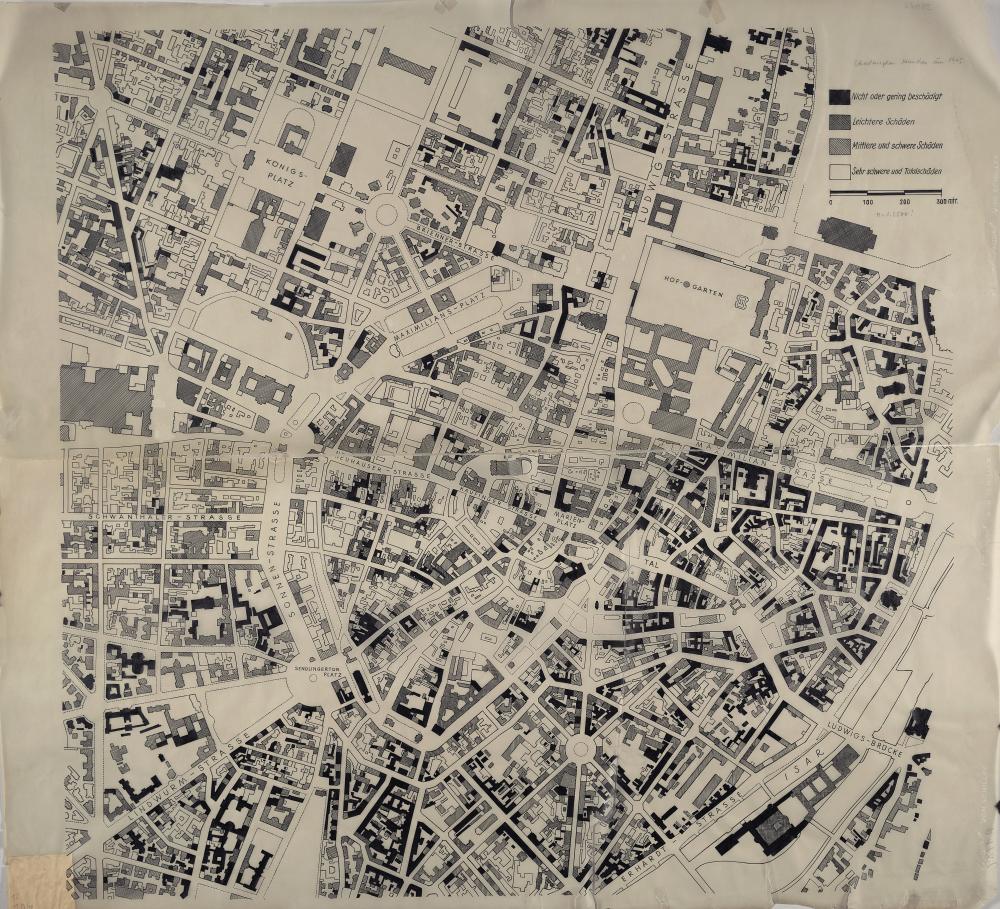

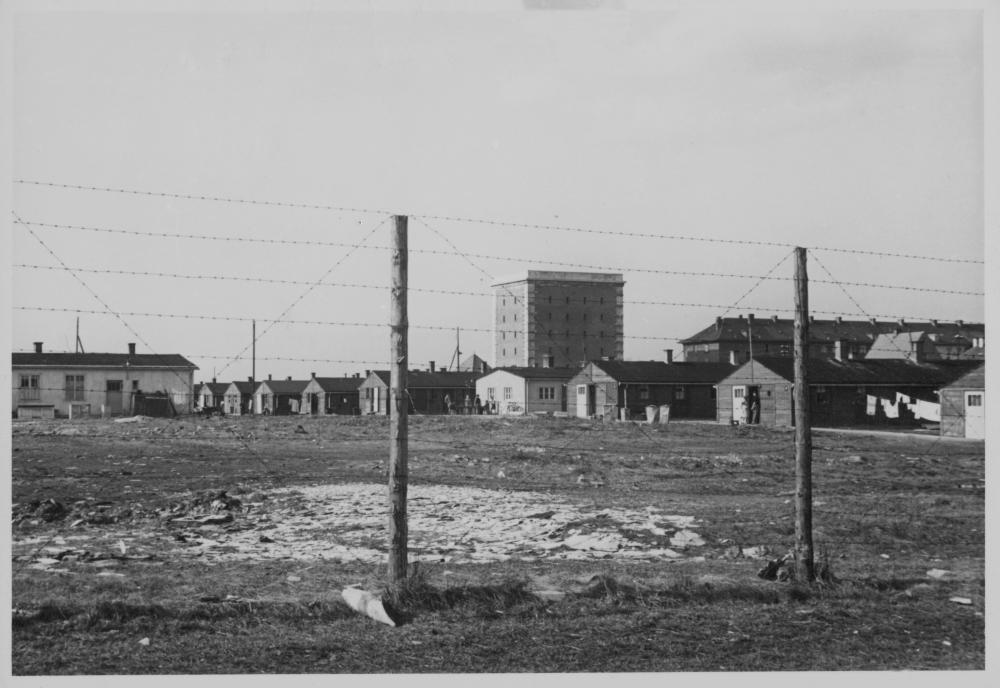

Though bullet holes marked the building’s facade, the bunker, despite being within the zone of wartime destruction resulting from the air raids on Munich, remained largely intact. Directly after the end of the war in May 1945, the US Army erected encampments around the bunker. In the following years, the grounds served as an internment and labor camp for former Nazi Party members including prominent leaders like the former chief mayor of Munich Karl Fiehler and Hitler’s personal photographer Heinrich Hoffmann. After 1948, the compound was briefly used as an encampment for refugees.

In the years 1984–85, in an effort to maintain its function as a shelter for the public, the World War II relic was outfitted as a completely sealed NBC bunker, protecting against nuclear, biological, and chemical threats. The end of the Cold War soon afterwards eliminated the need for bunkers of this kind, and a fitting use for this colossal hulk of architectural heritage became increasingly unclear. As was the case with other air-raid shelters from the Second World War, the debate over demolishing or maintaining the structure could easily have led to a long term deadlock. However, another solution revealed itself: shortly after the building received landmark status in 2010 as a structural testimony to the Nazi era, Munich entrepeneur Stefan F. Höglmaier (Euroboden GmbH) acquired the troubled property in Nordschwabing.

2010 until today

At this time, the seller, on behalf of the federal government, had neither a concept for the building’s continued use nor the historical requirements permit or construction permits necessary to alter its structure. However, the ambitious proposal from Stefan Höglmaier to bring this important testament to Munich’s history into the future and transform it into a mixed-use building with apartments, offices, and exhibition spaces convinced all concerned parties. Höglmaier commissioned the Starnberg-based architectural office raumstation Architekten (Fränzi Essler, Tim Sittmann-Haury, Walter Waldrauch) to oversee the spectacular renovation, which took place in the years 2012–13. Beyond observing its identity as a memorial to a harrowing past, it was important to handle the structure in a manner that anchored it culturally in the future and allowed it to play a role as a generative part of urban society. In this interest, the private premises remain open to the city surroundings and maintain, through the deliberate design of the outdoor spaces, in the truest sense, the function of a monument.

Formerly accessible only through sealed, airlock gates, and with fluorescent tubes scarcely lighting the bare concrete walls, the building now hosts the BNKR exhibition spaces; apartments and commercial spaces in the upper floors; and a glass-enclosed penthouse level. In total, the building has about 2,000 square meters of floor space. The renovation measures were possible through a particularly precise intervention: in every story and in every direction, the excision of three-meter-square sections of the two-meter thick walls created floor-to-ceiling openings in the facade. This required the removal of around two-thousand tons of reinforced concrete: a tremendous exertion of force that is visible in the massive blocks that lie freely arranged around the bunker’s grounds.

Observing a fundamental principle to not deny history and instead make it a visible focus of inquiry runs throughout the structure’s entire design concept. The facade may be clean, but the bullet holes from the war remain. In the building’s interior, traces of the past appear at every step, whether in the completely original stairwell or other intentionally preserved details, like the sandblasted, solid concrete ceilings.

BNKR’s exhibition spaces are located in the ground and lower levels. In these rooms, contemporary art is the focus, with presentations in intimate galleries without distractions or gimmicky interferences. Slanting window soffits create an almost sacral atmosphere where earlier only darkness dwelled; they introduce an architectural imperative that informs the development of any new curatorial concepts: to support and illuminate current reflections on art and architecture.

Sources:

- Dürr, Alfred. Baukulturführer 81. Hochbunker München. Edited by Nicolette Baumeister. Munich: Koch, Schmidt & Wilhelm, 2017

- Freund, Madeleine. “The Bunker at Ungererstraße 158 in historical context.” In: The Architecture of Deception / Confinement / Transformation, edited by Sam Bardaouil and Till Fellrath, 60–77. Milan: Silvana Editoriale, 2021. Exhibition Catalogue